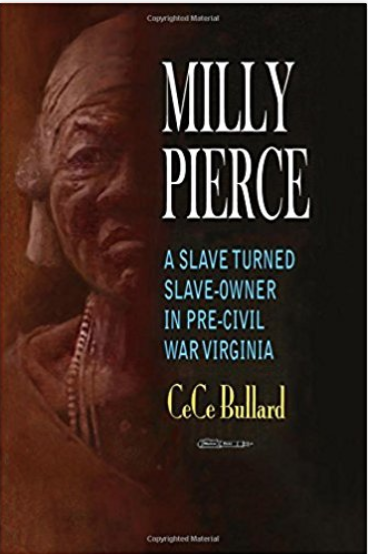

Milly Pierce: A Slave Turned Slave-Owner in Pre-Civil War Virginia

By CeCe Bullard

Black, female and on her own, Milly Pierce embodies in many ways the long, complex and convoluted quest for equality that continues to characterize the odyssey of American women and minorities. This astonishing true story of an enslaved woman who won her freedom and found that the only way she could survive was to herself become a slaveholder echoes the themes of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Edward P. Jones, The Known World. Milly Pierce did not merely survive white oppression, she made a place for herself in the white power structure—and prospered as a “free woman of colour” rather than a freed slave. She did not accept her freedom meekly as a gift from her white master, she claimed that freedom as her own natural condition. As the Virginia legislature imposed new restrictions on free black citizens’ right to work, to education, to worship, to assemble and to trial by jury, Milly Pierce literally held her ground, the first black woman to own land in that part of the state, and thriving as an astute businesswoman. CeCe Bullard’s meticulously researched book tells her story for the first time.

Milly’s life is the backbone of this story, but not the whole story. Her life was framed by the two defining moments in this nation’s history. Milly walked away from slavery and secured a comfortable life for herself and her family, despite growing hostility and limitations on her freedom, during the same period in which the country moved from the idealism of the war for independence to the disillusion of the Civil War. A beneficiary of the revolutionary faith in freedom, she was a precursor of the war for her race’s liberation. Black, female and on her own, Milly embodies in many ways the long, complex and convoluted quest for freedom that continues to characterize the odyssey of American minorities.

Milly’s life mirrored the national landscape; but it was also deeply rooted in a particular time and place. Life in a sparsely populated, rural county such as Goochland was a tightly woven tapestry of constantly intersecting lives. What renders Milly’s story especially rich and rewarding is not merely the single thread of her life, but also the several stories of her extended family and neighbors which both weave through and lead beyond her own. Collectively, these stories both reinforce the central, peculiar realities of all free black lives and highlight the myriad ways in which individuals either transcended or succumbed to the pressure of unremitting prejudice.

During her eighty years, Milly, like every free person of color, was subjected to increasingly restrictive and sometimes punitive laws designed to limit the freedoms of the not-quite-free black population and to restrict its growth. As the prevailing degree of white paranoia rose, Virginia’s legislators tightened the vise. In the course of Milly’s life, she lost the right to travel freely, the right to worship as she chose, the right to assemble, the right to an education, and the right to trial by jury. By the time the opening shot of the Civil War echoed across Charleston harbor, free blacks had lost many of their basic rights; their freedom, although severely compromised, was almost all they had left to lose.

While the strictures of the law forced many free blacks to abandon their homes or suffer re-enslavement, others, overwhelmed by unaccustomed challenges and responsibilities, saw freedom slip through their fingers and were reduced to involuntary servitude. A few, like Milly, held their ground (both literally and figuratively) and made the most of their precious, if fragile and imperfect, freedom.

Survival for free blacks was, perhaps above all, a question of character. Eventually, slave owners were allowed to manumit only those slaves who demonstrated “extraordinary merit and general good character and conduct.” Character, however, was much more than a question of statutory law for free blacks in ante-bellum Virginia. To negotiate a maze of crippling and entrapping laws, a free black must have possessed iron will and extreme patience. To win the acceptance of the white community, a free black must have been constantly working, honest and responsible. To face a hostile world bent upon her destruction, a free black must have drawn on deep reserves of courage. Simply to be tolerated, a free black had to be above reproach—a standard far from foreign to today’s African Americans.

Milly shouldered not only the burden of her color, but also of her gender. To be both black and female was to live in double jeopardy. When Thomas Jefferson declared “all men are created equal” he really meant all white males. A woman’s economic survival, regardless of her color, most often depended on a good marriage, yet marriage marked the end of her legal and economic independence. Milly Pierce remained by choice unmarried and in control of her own destiny, and she took full advantage of those few rights granted her. She availed herself of the right to work for wages and the right to own property and achieved economic security for herself and her family. She did precisely what the white patriarchy wished to believe was beyond the capabilities of a woman and a former slave.

Milly Pierce did not merely survive white oppression, she made a place for herself in the white power structure—and prospered. Milly Pierce was truly a “free woman of colour” rather than a freed slave. Somehow she turned a critical corner when given her freedom: she did not accept her freedom meekly as a gift from her white master; she claimed that freedom as her own natural condition. Faced with a freedom that was fraught with both promise and fear, Milly Pierce proceeded to piece together her own peculiar life—a life that actually bridged the great divide between black slave and white master—and make it work.

- CeCe Bullard