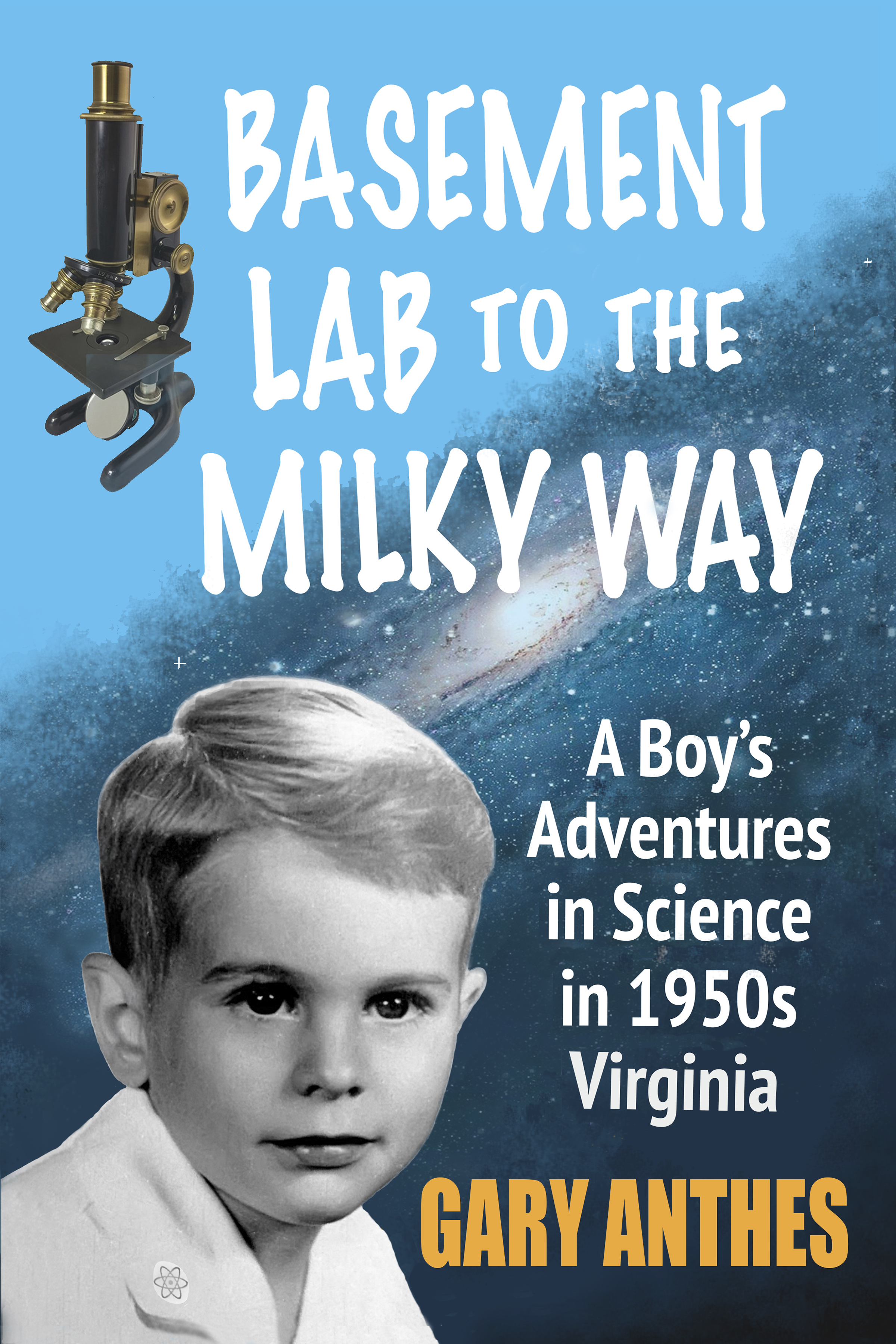

Basement Lab to the Milky Way: A Boy’s Adventures in Science in 1950s Virginia

By Gary Anthes

Memoir of a science-minded kid growing up (and sometimes blowing up) in a small town in 1950s Virginia

The Soviet Union launched its Sputnik earth satellite in Oct., 1957, triggering a massive effort in the U.S. to develop its own space program. My brother, Ricky, and I were already working on rockets, and while NASA used kerosene and liquid oxygen for propellant, we had to make do with gunpowder. For awhile we made our own by mixing powdered charcoal, saltpeter, and sulfur, but it was hard to get a uniform mix, and it burned unevenly.

Gunpowder was one of the few things that could not be ordered by mail, even then, but we found a source at the local Brooks Sporting Goods store. One pound of DuPont Superfine Gunpowder – a beautiful silvery gray blend of ingredients priced at $1.25 – came in a bright red oval can and was sold to hunters who wanted to refill their shotgun shells. I would go into the store, stand extra tall in order to see over the counter, and ask Mr. Brooks for a can of his best gunpowder, and he was happy to supply it, no questions asked. No doubt he thought Dad was waiting for me outside in his pickup truck, with his guns, dogs, and duck decoys.

Having solved the fuel problem, next came the ignition system. Home-made fuses that were lit by a match were tried but were unreliable. (Also unsafe, not that we gave safety much thought.) So we cut the female end off an extension cord, stripped an inch or so of insulation off of each wire, then placed a thin copper wire across the two ends of the cord. The copper wire was inserted into the base of the rocket, touching the propellant. When the cord was plugged into a wall socket, a surge of electricity would send an incandescent spark through the copper wire, instantly vaporizing it and setting off the rocket fuel. The beauty of our approach was that it enabled us to retreat to the safety of our basement and watch the launch from a command bunker, not unlike NASA’s control centers.

The navigation system proved trickier. We aimed the rockets carefully, but because they had crude cardboard fins, they were apt to veer off course. Ricky recalls, “Sometimes the rocket just blew up. Other times it would lift off and spiral crazily out of control until it crashed and burned. But one time we got a perfect launch and the thing sailed off on a beautiful arc toward the north and landed in an overgrown vacant lot behind our yard.” We were delighted, until we saw smoke and flames in the field.

By the time we realized what had happened, the fire was well underway. We were fortunate in having a garden hose long enough to get way back there, and with some water and foot-stomping we put out the blaze. We were hailed as heroes by a neighbor who had seen the fire, but not the rocket, and didn’t know our role in it. She invited us into her house for cookies and pats on the back, both gratefully accepted by us.

And yet, I felt a little guilty about this particular caper, not for having started the fire but for having taken credit falsely for extinguishing it. Even now when I tell people of my boyhood adventures, I tell this one reluctantly.

- Gary Anthes