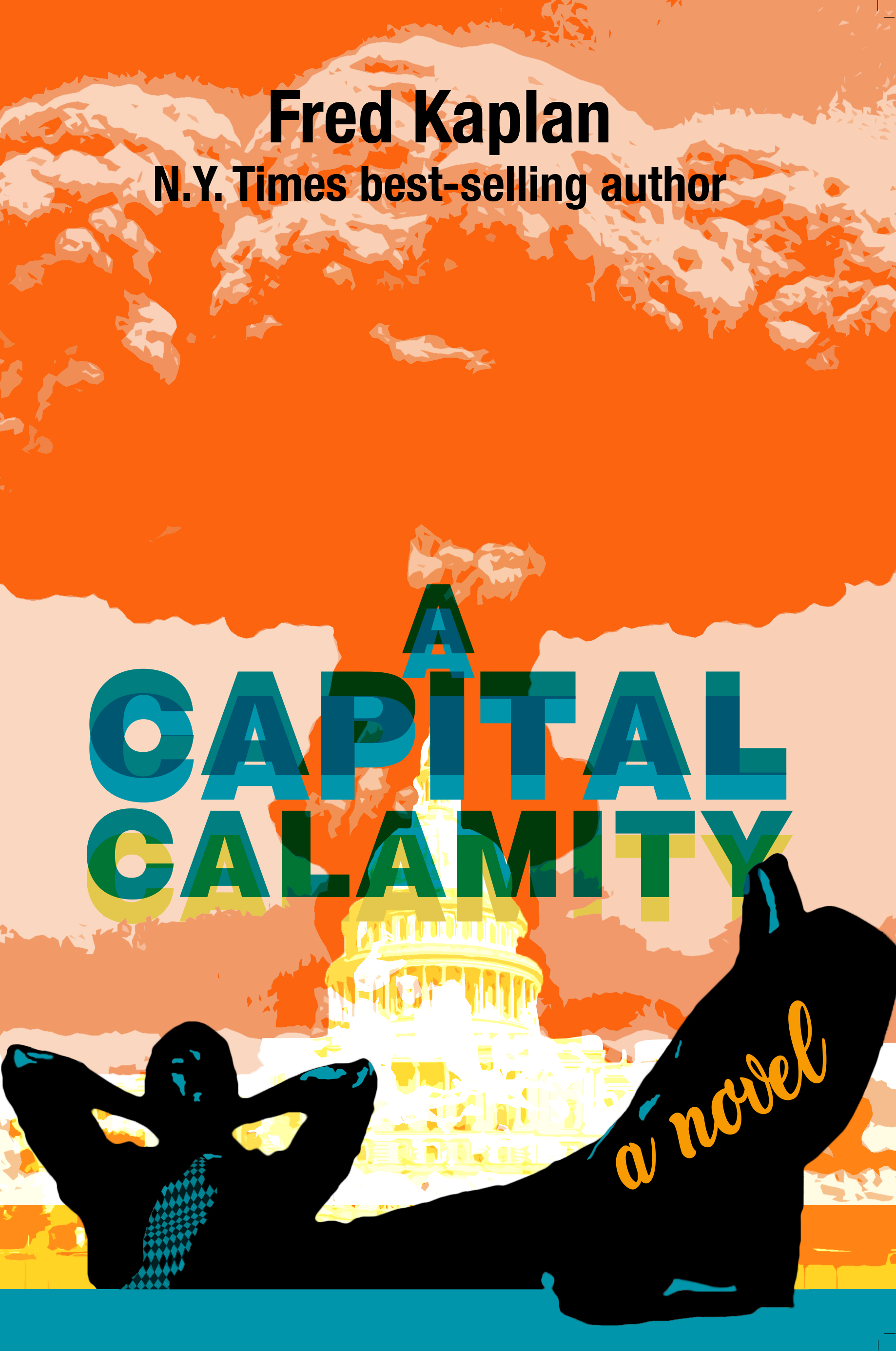

A Capital Calamity

By Fred Kaplan

A CAPITAL CALAMITY – A Novel by Fred Kaplan

“Serge Willoughby just wanted to make money and have fun. He didn’t mean to start World War Three.” So begins A Capital Calamity, the rollicking debut novel by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and New York Times best-selling author Fred Kaplan.

The “War Stories” columnist for Slate, author of six books, mostly about national security (including The Insurgents, which was a N.Y. Time best-seller and a Pulitzer Prize Finalist), Kaplan draws on four decades as an insider-outsider observer in this tale of manners—both satire and thriller—about the Washington scene. (The prologue reads, “Much of what follows is true, except for the plot”), it tells the story of a cynical defense consultant whose mischief plunges the world into a cataclysmic crisis. Now, along with the CIA director (who is also a bitter ex-girlfriend), a former school chum who’s now an NSA hacker, a garrulous Wall Street tycoon-turned-secretary of defense, and a beautiful intrepid journalist (who may or may not be flirting with him for a big story), Willoughby must now end the crisis, though he has spent his life avoiding commitment to any political cause or purpose. A Capital Calamity is a funny, trenchant, deeply moral novel, in the spirit of Thank You for Smoking, Our Man in Havana, and Dr. Strangelove. <P><P>

Advance praise for A Capital Calamity:<P><P>

“A joyful romp! Just when we need satire more than ever, one of our best political commentators has morphed into a brilliant and irresistible comic novelist.”<P>

JOE WEISBERG, creator of The Americans<P><P>

“Fred Kaplan’s new book gives us comedy, treachery, ideas, and shrewd cultural anthropology—all against a page-turner background of the highest-stakes international showdown. It’s like the cast of Veep in a Tom Clancy book. Readers will learn a lot, and have fun while doing so.”<P>

JAMES FALLOWS, former chief White House speechwriter, author of National Defense and other books<P><P>

“Kaplan pulls back the curtain hiding how Washington really works in this only slightly exaggerated, darkly humorous look at ‘national security’ and ‘unthinkable’ nuclear war. Sometimes you can tell more truth through fiction, and this true fiction is fun.”<P>

RICHARD A. CLARKE, former White House counterterrorism chief, author of Against All Enemies and The Scorpion’s Gate<P><P>

Q&A with FRED KAPLAN, author of A Capital Calamity

You’ve written six acclaimed non-fiction books. Why did you decide to write a novel?

The COVID lockdown struck about a month after The Bomb, my last book, came out. All of my books have been based on in-person interviews and research at archival libraries. This was suddenly out of the question. I was keen to start another book. A novel wasn’t so farfetched. My other books have told stories. And for many years, I’d had an idea for a novel. So, I gave it a go.

Is A Capital Calamity pretty much a realization of that idea?

Well, it starts out the same way. A cynical defense consultant goes to a party. He hates the host, gets on the phone, dials a number, and says something that activates a government wiretap, which lands the host in jail and starts a war. Beyond that (and this was about 35 years ago), I didn’t know where the story would go. Why is he cynical? How does this act of mischief start a war? Then what happens? It was fun to play these questions out; the creative process was different from anything I’ve been through.

Is writing fiction different from writing non-fiction? Is it harder?

Very different and, for the most part, harder. A friend of mine, who’s also a journalist, told me while he was writing a novel, “This is easy! You just make stuff up!” But actually, making stuff up—and having it make sense—is hard.

One rule of fiction that I read somewhere goes like this: A plotline can’t be “And then, and then, and then.” It has to be “And so, and so, and so.” In other words, the plotline has to be a line, the elements have to connect, and the line has to be drawn by and through characters. That involves a whole other way of thinking and writing, especially for someone, like me, who has never made up anything.

You’ve been a journalist for 40 years, much of that time covering the national-security world. Is the novel based on real people or real events?

The prologue reads “Much of what follows is true, except for the plot.” Yes, I drew on a lot of my experience and observations as a sort of insider-outsider in that world. A lot of the characters are composites of real people, many scenes depict actual events; details and generalizations are true-to-life; in some ways, it’s a how-Washington-works novel.

What are some examples?

Early on, our hero Serge Willoughby tells someone, “Just because something is classified doesn’t mean it’s true.” In real life, Dan Ellsberg, back when he was still a defense analyst, said that to Henry Kissinger as a word of advice when Kissinger became Nixon’s national security adviser.

Another example: The secretary of defense in my novel, James Weed Portis, prepares for a congressional hearing not by rehearsing his testimony in a calm voice but rather by barking out the foulest obscenities, so that he can get it all out of his system. Robert Gates, who was Bush and Obama’s defense secretary, wrote in his memoir that this is what he used to do, he so hated appearing before Congress.

I should say, Portis is based a bit on Gates, but also a bit on Robert Strauss, a big time Washington lawyer who was Ambassador to Moscow when I was a reporter there in the mid-1990s, and a bit on an old graduate-school professor of mine named William Weed Kaufmann.

Another example: At the start of the book, Serge walks into a party where the guests are scattered in a tribal pattern: the spies in one corner, diplomats in another, Pentagon officials and arms manufacturers scrambling back and forth, making lunch dates. That’s the way these Washington parties work. Many descriptions of weapons technology, fanciful threat-scenarios, the interservice rivalries and petty squabbles that drive this whole peculiar Washington subculture—it’s the real deal.<P><P>

What is a defense consultant?<P><P>

A defense consultant is someone who solves problems that his clients—usually weapons manufacturers and the armed services—can’t by themselves. He basically sells their product by coating them with a veneer of mathematical precision and analytical rigor that makes them seem essential to national security. Serge is one of the best, but he also has a peculiar MO. He plays both sides of the street in order to make double the money. In other words, he will do a pro-bomber study for the Air Force (which makes nuclear-armed bomber aircraft), then an anti-bomber study for the Navy (whose admirals think all we need for nuclear deterrence are submarines). He calls his consulting firm the Janus Corporation, named after the Roman god with two faces. His entire life is soaked in cynicism. When he was a young man, working on Capitol Hill, he discovered that the legislators voted according to whim or gut feeling, not strategic thinking—that his complex quantitative analyses were just a rhetorical cover. He was very disillusioned by this.

But as we learn later in the book, his cynicism has deeper roots as well.

Is Serge Willoughby based at all on you?

Well, like Serge, I studied arms control and defense policy at M.I.T. grad school, then went to work as a foreign- and defense-policy adviser on Capitol Hill. He and I have similar tastes in art, music, and design. We both like jazz, basketball, urban street photography, and stand-up comedy. But I’ve never been a consultant, I don’t think I’m cynical (I am skeptical, sometimes a bit dark, but I believe in ideas and I have principles).

I’m more committed personally as well. Serge’s romance life is fleeting; I’ve been married to the same woman for 41 years. But the story has an arc. It’s about how this shrewd cynic is transformed to a global citizen with a sense of purpose. <P><P>Part of this happens by immersing himself in a crisis—realizing that he’s the cause of the crisis and so must help solve it—and by seeing that, sometimes, rational analysis can change the world. As his mentor, a fellow consultant named Giles Molloy, tells him at one point, Yes, much of this world is a joke, but it’s not just a joke, and we have a responsibility to use our talents and our position to speak truth to power. And at the same, Serge grows attached to a woman, an investigative journalist who also goes through her own evolution, in the end abandoning her lucrative elite newsletter and returning to her old job at the Washington Post, because she realizes that war and peace are too important to be left to an elite, that the general public needs to be informed.

So, this is a moral tale?

In part. It’s also funny and suspenseful—sort of a satirical thriller. I was inspired by a mix of Dr. Strangelove, Thank You for Smoking, Three Days of the Condor, and Our Man in Havana. All of those works are moral tales too, in the sense that they’re about the need to plant stakes in the world. But they’re not moralistic or sentimental.

Near the end of the novel, the CIA director (who’s also an ex-girlfriend of Serge) asks him if he’s had enough adventure, and he replies, jokingly, that he’d like to try his hand at making peace in the Middle East.

Will there be a sequel, perhaps a Serge Willoughby series?

Ha! We’ll see.

Lawrence D. Freedman

From Foreign Affairs:

As an experienced observer of the entanglements in Washington between policymakers and think tanks, Kaplan skewers the Beltway effectively in his satirical novel, a thriller and morality tale that affords some light relief in dark times. The defense consultant Serge Willoughby plays a prank on his host at a Georgetown party that completely backfires to the point that not only is the host arrested but also skirmishing between the United States and China begins and World War III looms. Working closely with the director of the CIA, an ex-girlfriend, a possible future girlfriend, and others, Willoughby helps defuse the crisis. The hero represents the greed and cynicism of the Beltway; his consultancy specializes in studies that help one U.S. military service make a case for a new weapon—while providing another service with the case against the weapon. But Kaplan affords his protagonist a measure of redemption. The author claims that the plot is made up, but the knowing reader will recognize aspects of the main characters and events in contemporary figures and historical episodes.

Serge Willoughby just wanted to make money and have fun. He didn’t mean to start World War III.

It began, as many calamities do, at a Washington party, in this case a gathering of the national security community—a deceptively collegial term for the flock of officers, spies, and corporate mavens that formed what was known in less euphemistic times as the military-industrial complex.

Willoughby came to these parties because he had to. For he was a consultant, someone who made considerable sums of money by solving problems that his clients—mainly the military services and the weapons manufacturers—couldn’t solve by themselves, or, rather, couldn’t solve in a way that convinced the budget-masters in the Pentagon or Congress to buy their wares. In short, a good consultant—and Willoughby was one of the best—supplied the veneer of intellectual heft and mathematical precision that clients needed in order to boost their fortunes or, in some cases, stay alive. And these parties were where the gossip first circulated on which big weapons programs were in the lineup, who would be the sources of resistance, and what sorts of arguments might alter their views.

So, Willoughby walked into this particular party, on a warm, early autumn Sunday evening, in a characteristically blasé disposition, as if nothing was out of the ordinary and the world wasn’t about to take a cataclysmic turn. He looked around the expansive living room and saw that the guests had coalesced into the usual tribal pattern. Huddled in one corner were the intelligence analysts: expressionless, bedecked in suits that were perpetually out of fashion (which, in this season, meant wide lapels and diagonally striped ties), whispering to one another through the corners of their mouths in codewords and acronyms that no one else in the room knew existed. Nearby were the foreign diplomats, more colorful in couture and demeanor, chuckling about some breach of esoteric protocol, one of them sauntering over to the spooks’ corner for a brief exchange, a clear sign that he was the undercover spy at his embassy. Spanning the middle of the room, with nothing to hide, were the lobbyists and the defense contractors, exchanging phone numbers, setting lunch dates, grabbing the shoulder of a congressman or midlevel Pentagon official, crisscrossing the room from the wine-and-booze bar to the fruit-and- nuts bowls to the cracker-and-cheese board and back again, pitching, pleading, and kowtowing to would-be customers.

Willoughby, who routinely flitted among all these clans with equal parts familiarity and disaffection, was mulling which way to turn when a Navy vice admiral approached him.

“Serge!” he called out in high spirits. “You’ll be getting the contract for that analysis tomorrow. And listen, the chief wants no surprises.”

“Only two things would surprise me,” Willoughby coolly replied. “First, if any of you guys in the Pentagon wanted surprises. Second, if you ever paid my bills on time.”<P><P>

Willoughby moved toward the wine table but was intercepted by an aerospace executive. “Hey, Serge,” he said with brow- furrowed seriousness, “are you going to bid for that study on the cost-effectiveness of a shoulder-fired hypersonic glide vehicle?”<P><P>

Willoughby grunted. “I do stupid, and I do science fiction,” he said, “but I don’t do stupid science fiction.”<P><P>

- Fred Kaplan