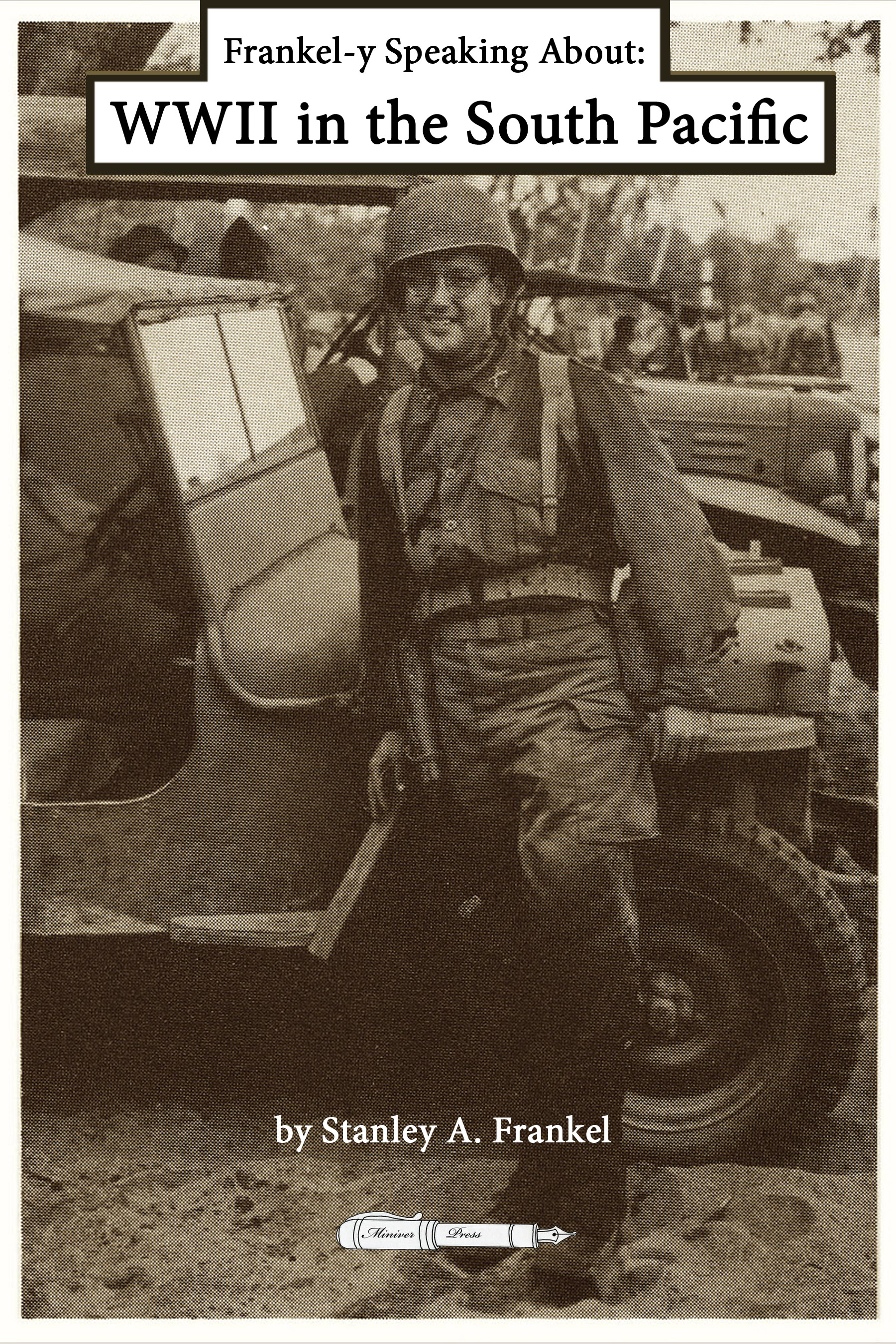

Frankel-y Speaking About WWII in the South Pacific

By Stanley A. Frankel

Stanley Frankel didn’t want to be a soldier. But the draft board had different plans. The leader of college protests against the US entering WWII found himself in the 37th Infantry Division, shipped to the Pacific Theater. While in the army, he wrote journal entries, letters to his dear Irene, and articles that slipped past the censor to be published in newspapers and magazines in the US while the war was raging. Frankel served from 1941 to 1946, and was then ordered to stay on after the war as part of a team tasked with writing the historical account of his division. After that he became a successful advertising executive, award-winning professor, political speechwriter for national candidates, and beloved husband, father, and grandfather.In this memoir,

Frankel tells his story interspersed with in-the-moment journals, letters, and articles he wrote while stationed in the Pacific. Take a journey through time with this raw first-hand account, and experience what it was like to be in the jungles and battles of an intense and brutal part of World War II. In his later writings, see the post–World War II world through the eyes of a veteran selected as the official historian of his division.

Unforgettable stories leap off the page, from the chilling to the hilarious. Feel the terror as an explosive flies through a window into a huddle of soldiers. Laugh at the account of soldiers delighting in the discovery of an abandoned factory flooded with ice-cold beer. Frankel describes serving alongside Private Rodger Young who gave up his life in New Georgia to save 20 men of his patrol and inspired a song. He brings us into the Rescue of Bilibid Prison, and the battles of Bougainville and Guadalcanal.

This is a wise, honest, and beautifully written book for anyone who has wondered about the realities of combat, the journey of shouldering a duty you did not choose, or the experience of being among the “greatest generation” who came of age in the Depression and fought in World War II.

This edition features a new introduction from Frankel’s grandson Adam, who followed in Stan’s footsteps to become a political speechwriter, including writing speeches for President Obama in the White House, and who is now an author himself, with his family memoir, The Survivors.

| I |

was drafted into the U.S. Army on January 23, 1941, ten months before our nation entered World War II. I was assigned to the 37th Ohio National Guard Division. A very reluctant soldier, I believed, as did most of those drafted with me, that I would serve no more than twelve months. Five years and five major battles later I was discharged with the rank of major.

Like most American men in my generation I was not brought up to be a soldier. My first twenty-three years ill-prepared me to be plunked down as a World War II infantryman for 3½ years—in the dank jungles of the Solomon Islands, in the lethal streets and buildings of Manila, and on the frightening, winding mountain roads leading up to Baguio in the Philippines. Those who knew me in Dayton, Ohio, where I grew up, and at Northwestern University where I led student rallies calling for non-participation in the war in Europe, surely would have thought it wildly unlikely that I would become an officer in the U.S. Army in the South Pacific leading troops into battle.

The chapters in this book are my own personal account of what might be called “Frankel’s War.” They are based on recollections and materials written at the time. Many of the chapters are accounts in the form of letters drafted immediately after combat ceased, red hot on a borrowed typewriter, and sent to a “Dear Aunt Madeleine” in New York City. Aunt Madeleine was really Ms. Madeleine Brennan, a top literary agent, who had been persuaded by my father-in-law to be, Salem Baskin, to read and, if warranted, try to sell what I had sent her. Some of these she managed to get published; the balance have been in my files for all these years, carbons on onion-skin paper of the originals I had sent to “Aunt Madeleine.”

Then there were personal letters. During my entire service, my college sweetheart and almost-fiancée, Irene Baskin, to whom I had given my fraternity pin and Phi Beta Kappa key, wrote me every other day, and I responded faithfully and regularly. These letters to her, exactly 1,232 of them, she kept in loose-leaf notebooks and presented to me on my return from the Pacific in January 1946. (We were married February 20, 1946.) Rereading these letters 45–50 years later called to mind many hundreds of half-forgotten incidents and triggered some of the materials that follow.

Those of you familiar with the ways of the army in World War II may wonder how I managed to send materials like those to “Aunt Madeleine” to the States uncensored. At first I had few problems. All outgoing mail written by enlisted men was censored by their immediate commanding officer (quite an inhibitor to the love-and-action comments of the soldiers). Letters from officers were censored in random fashion by the Army Post Office in the field, the usual hit-or-miss affair resulting in few hits and many misses.

For a long while all my letters got through, untouched. Eventually, however, when some of my stuff started being published in the States in newspapers and national magazines, clippings would often be relayed by the loved ones back home to the commanding general, colonels, and others.

Articles intended for publication were supposed to be submitted to the Division G2, a procedure I had not wanted to risk because of my apprehension that I would be denied permission. When the top brass did get wind of my publications, they did not make an issue with me about my breach of army regulations. But thereafter the Division Post Office examined every Frankel letter carefully. Irene began to receive V-Mail with words and sentences clipped out. One, she recalls, had a sentence beginning: “I am on an…(next word scissored out).” It didn’t take her too long to fill in the missing “island.” Later, after I found out I was being censored, I resorted to some tricks to slip out information. Once, trying to let her know where I was, I asked her repeatedly about a “mutual friend, Helen.”

Irene wrote back, “Which Helen?”

I then replied, “The Helen who was a sorority sister of yours at Northwestern.”

She answered, “Do you mean Helen Goldberg or Helen Solomon?” And she further wanted to know why I had suddenly evinced an interest in them, since we had not been particularly friendly with either.

I reacted: “No, not Helen Goldberg. The one I really want you to concentrate on is the other Helen.”

At that, Irene figured it out that I was trying to tell her we were in the Solomon Islands.

In addition to the letters to Madeleine Brennan and to Irene, I had my diary, which triggered many memories. Keeping a diary was forbidden, but I had kept one nevertheless, in my back pocket during combat, hidden in my footlocker between missions. This diary served as the source of several of these chapters.

- Stanley A. Frankel